Dance of the emergent self

Today I watched a wonderful dance performance by the Royal Ballet. It was a piece by choreographer Alastair Marriot called ‘Connectome‘.

Connectome has a thoroughly scientific premise. It’s based on the 2012 book of the same name by Dr Sebastian Seung, a Professor of Computational Neuroscience at MIT. Dr Seung argues that our human identity doesn’t lie in our genes, but in the connections between our brain cells – our own particular synaptic wiring, or “connectome”. His argument is that we are far more than simply genetic code; we emerge instead as distinct selves from the networked interrelations between our brain cells – shaped as they are by human experience: love, pain, laughter, loss.

It’s an argument for the perfect complement of art and science – the self as a cultural and psychological entity emerging in glorious analogue from the digital core of our coded biological data. Forever irreducible to those coded parts, but with a mind now able to describe and articulate the biological elegance that begat it.

One choreographic image stays with me. It’s the very opening of the ballet – brilliantly designed by Es Devlin. The stage is populated by rows of closely packed vertical steel tubes. Onto the tubes are projected patterns of  irregular light and shade that bring to mind the genetic strip test samples familiar to genetic laboratories. Our coded selves. Within these flashes of light and shade we can make out the dark shapes of male figures – still and robotic against the light of the tubes. A constructed sum of these parts.

irregular light and shade that bring to mind the genetic strip test samples familiar to genetic laboratories. Our coded selves. Within these flashes of light and shade we can make out the dark shapes of male figures – still and robotic against the light of the tubes. A constructed sum of these parts.

Just then, we detect a trace of movement between the strips. A flash of white. It takes our eyes a few seconds to make out a shape between the tall, cold steel trunks. Then we see it again. It is a solo female dancer – an individual human being – negotiating the forest of code, leaping and dancing between the bands of light and the dark stillness of the male shapes.

She is us. Skipping through the elements of the reality that describes her, but which cannot contain her. She is alive and doomed. Rational and erratic. Joyful and sad. Driven by interaction with her world, and the emotions they engender. She is imagination, fancy, creativity.

The mistake is to think she is dancing alone. She isn’t. Those coded strips represent her dance partner – holding her steady as she leaps. The essential stillness of the data that gives her movement a human blood and passion. There can be no leaping of the imagination without the canvas of reality on which to paint it.

There is a rich tradition in science communication for formal collaboration between art and science. It’s founded on the sincere premise that these two great traditions can take something from each other by their occasional polite proximity. Rather like a friendly but cautious summit meeting of two distant superpowers.

I prefer to think of the relationship between art and science as integral. A dance between two aspects of the same personality. The same reality viewed from different angles. They are not distinct – rather science raises and holds art to a height above its head by which art can describe the beauty of their collective nature. A human nature. It is the dance of the emergent self.

A duet.

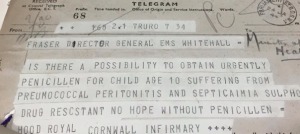

My friend Jessamy Carlson, an archivist and researcher at the UK’s National Archives, has just posted a fascinating blog entitled ‘No hope without Penicillin‘. Jess and me share an interest in the administration and production of penicillin in the late stages of World War 2 – which heralded the dawn of the antibiotic age of public medicine.

My interest began as a very personal one: my father’s life was saved by the use of Penicillin on his wounded body in the D-Day invasion. Its early production in 1944 was confined exclusively to the war effort. Only when peace came did the general population begin to know the extent of this medical miracle – and its ultimate limits.

Jess focuses on particular UK government correspondence in those weeks leading up to the first widespread use of the drug. What’s fascinating is that the rumour machine is in full swing – the medical community knows that something big is coming, and their desperation for this new wonder drug is evident. The papers report that inquiries are flooding in from medics far and wide, begging access to this new drug for treating their desperately ill patients. In one moving telegram, a doctor pleads for the life of a child with peritonitis and septicaemia, aware that penicillin is the only thing that might save them. Yet the authorities must withhold the drug for battlefield use.

Another interesting aspect is that knowledge of Penicillin’s efficacy has not yet been fully established – with some believing it might be effective in treating diseases like cancer or leukemia. Yet for me the most arresting item is the prescient remark made by Sir Edward Mellanby (of the Medical Research Council) On the 7th December 1943, who wrote:

“No substance can be more easily wasted, especially if it is poured into patients by systematic treatment”

Mellanby was talking about the risk of antibiotic resistance. Even before the antibiotic age had begun, there were those who worried that we may come to regret squandering this rarest of medical miracles…

Take a look at Jess’s post here:

Dreaming spires and the popular imagination

Archaeologist Indiana Jones, played by actor Harrison Ford, Raiders of the Lost Ark, 1981. Photograph by AF archive, Alamy

I was pointed to a thought-provoking article on National Geographic this morning, entitled “How Indiana Jones Actually Changed Archaeology“. The article accompanies an exhibition at the National Geographic Museum in Washington that celebrates the famous Spielberg movie franchise and – interestingly – both its contribution to, and debt to, real-world archaeology research.

Also interesting were the Twitter comments of the person who posted the link to this article. It was Professor Francesca Stavrakopoulou, Head of Theology and Religion at Exeter University in the UK, who said – “As a kid, Raiders of the Lost Ark & Temple of Doom definitely played a part in shaping my love of ancient religion.”

She wouldn’t be the first eminent academic who identified a popular cultural text that fired an early enthusiasm for their specific field. My work in Science Communication has led me to many conversations with science-fiction inspired scientists – or medics who never missed an episode of their favourite TV hospital drama. Yet the subtle symbiosis between popular creative culture and the academic work it can both inspire and feeds off is, in my view, too rarely acknowledged or accommodated.

Recently I chatted with an academic about my belief in the power of popular narrative to allow our society to ‘think out loud’ about human problems or aspirations that have an academic dimension. As I explain in this recent article for the JRSM, I believe popular cultural narratives – even highly fictionalised – can enable an emotional engagement with academic meanings beyond the simple presentation of academic facts. The academic smiled kindly and, with a gentle wave of one hand, suggested that popular fiction or dramatic entertainment was tolerable as a basic means to “get the public through the door” of a serious institution or museum – after which, (I assumed) the proper work of real-world education could begin.

This, I felt, was not simply dismissive of the public as a sophisticated citizenry, capable of extracting valid meanings from popular cultural outputs, but also worryingly naive. It doesn’t just patronise – it fails to grasp the essential human interplay of public imagination and material reality, of emotional engagement and academic imperative, that defines the human relationship with reality.

As a society we dream, and create, and pray, and love, and pretend, and imagine, and dramatise. As the very same society we also study, and construct, and cure, and deduce, and calculate, and think. The idea that these essential human activities operate separately in our brains and in our society under a form of medieval feudalism – rationality and education the noble squire under which a serf-like popular imagination toils – is itself an imaginative fiction. Popular culture is not simply the child of an imagined public ignorance. It is, as Professor Stavrakopoulou suggests, the parent of our academic motivations.

We dream before we specify. We imagine before we do. But we do both – together and separately. We also do not ‘ascend’ from the consumption of popular cultural myth to hermitic rational wisdom. We extract insight from a shared ore of human experiences. The driest of our academic insights are distilled from the same human force that painted its hands onto the walls of the Cueva de Las Manos. That joyous bricolage of hands that the paint reveals made the first tools upon which our modern world was built.

Look at those hands. No individual statuses to be discerned amongst its subjects. Serving no clear evolutionary purpose. Inexact. Illogical. Unnecessary. Yet as immortal as the rock itself.

‘We are here. We feel. We dream.’

Perhaps the most poignant message in these walls is that the cultural distraction of these ancient people has now become the subject of serious research by our modern world’s academics. What was popular and shared has become the food for a detailed, rational analysis. Yet the hands of the experts who analyse are indistinguishable from the wild hands they study.

The following message marks a one-off break with my normal blog practice. It is not written by me, but by my young nephew, Harry – a busy student nurse in a hospital in the midlands of the UK. Harry felt moved to pen a message on the day of voting in the UK General Election. I felt his words deserved to be seen more widely – and this was the simplest place to make that happen. I have edited and changed nothing. The words are all his.

—

I hope whoever emerges as the victor of today’s voting has the dignity, honour and pride to acknowledge – truthfully – what our NHS is. I hope they will endeavour to put pilfered resources back into it – and place it back into the hands of the public.

As a soon to hopefully qualify student nurse, even in my comparably short time training I’ve held a hand of life as it passed, both peacefully and tragically. I’ve watched it begin, both dramatically and beautifully. I’ve watched it break, and then helped it heal. All while under the same word: NHS. And I’m not the only one. Just on my course alone I’ve met countless incredible student nurses and training doctors – all of whom will go on to be inspiring and admirable practitioners. We all want our NHS; and we all want to fight for it. For you. But we need your help, too.

If you’re voting today, just remember that you may one day be at its doors with your loved ones and your life may well be at it’s lowest point; but we, nurses, doctors, healthcare assistants, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, cleaners, caterers, countless other healthcare workers, us fellow human beings; will do our utmost best to make things right again for you. To make things normal again. Even if ‘normality’ is not an option, we will do our best to make it as comfortable and pain free as possible.

Don’t let the NHS be turned into a business.

We are not for profit. We are for life. Human life.

Harry Thomas

@_harrybo

—

Science in the public eye

On Friday I had the great and terrifying pleasure of presenting a keynote speech to the Imperial College Graduate School’s Annual Research Symposium.

I used the opportunity to share thoughts on a subject that intersects both my academic studies in science communication and my long career as an actor in TV, theatre and film. The subject was science communication in its widest public sense – in mass public culture, and through mass media.

I called the talk ‘science in the public eye’ – rather than ‘science in mass media’, ‘popular science’, or any other variation – because I believe that the concept of a mass-cultural “public eye” – somewhere where science is increasingly seen through communicators like Brian Cox or Stephen Hawking – has its own character and challenges, easily overlooked by those who wish to see science communicated most widely.